November 28th, 2024

114. Divorce and Remarriage - Matthew 5:32

In Matthew 5:32 the EHV translates:

31It was also said, “Whoever divorces his wife must give her a certificate of divorce.” (32But I tell you that whoever divorces his wife, except for sexual immorality, causes her to be regarded as an adulteress. And whoever marries the divorced woman is regarded as an adulterer.

31It was also said, “Whoever divorces his wife must give her a certificate of divorce.” (32But I tell you that whoever divorces his wife, except for sexual immorality, causes her to be regarded as an adulteress. And whoever marries the divorced woman is regarded as an adulterer.

The specific translation that raises questions is “causes her to be regarded as an adulteress.” Most other translations have something like “causes her to become an adulteress.” These other translations seem to make her a perpetrator of adultery. The EHV seems to make her a victim of adultery. Does the EHV lessen the sin of divorce and remarriage?

This topic is especially relevant for two reasons: 1) Our society is suffering much heartache and grief from the prevalence of easy divorce and serial remarriage. 2) In American Evangelicalism there is a controversy between two views of divorce and remarriage, which has spilled over to some Lutherans.

Since the time of the Reformation the near-consensus view of Lutheran, Protestant, and Evangelical churches concerning divorce and remarriage has been that it is God’s will that every marriage should be a life-long union of one man and one woman. Every divorce (that is, every legal dissolution of a marriage contract) breaks such a union and involves sin on the part of one or more parties to the divorce. A divorce establishes a legal (but not necessarily a moral) right to remarry. God’s foundational principle for marriage established at creation is that there should be no divorce, and therefore no remarriage, unless God has ended a marriage by the death of one of the spouses. There are, however, three New Testament passages that refer to exceptions to the general rule of no remarriage except where death has ended a previous marriage. The exceptions are that when one party has broken the marriage by sexual sin, the wronged party may remarry, and if one party has deserted the marriage, the deserted spouse may remarry.

There is a movement in Evangelicalism that claims that the centuries-long Evangelical consensus has been wrong. Remarriage after a divorce is never allowed unless one’s previous spouse has died. This is very similar to the Roman Catholic view that the offense that leads to exclusion from communion is not the divorce per se but any remarriage that follows the divorce. The divorce itself is not grounds for “excommunication,” but any remarriage that follows it is. Catholics, however, have created a loophole which allows for remarriage through a system of church-controlled annulments. An annulment declares that the first marriage never was a sacramental marriage and that the divorced person may marry without penalty. In this view, if the “marriage” that was ended by a legal divorce actually was not a marriage, the second marriage is not really a remarriage, but a marriage.

The dispute in Evangelicalism is a complicated dispute that involves technical points of Hebrew and Greek grammar and evidence from church history.

The Evidence

Those who reject all remarriage except after the death of a spouse examine three lines of evidence to make their case: 1) What was the view of divorce and remarriage that was dominant in the world in which Jesus and Paul taught? 2) Do the statements of Jesus and Paul disallow all remarriage except in cases in which the previous marriages of both parties were ended by death, or does the Bible allow remarriage when the first marriage was broken by sexual sin and malicious desertion? 3) What were the views of the ante-Nicene church on divorce and remarriage?

We do not have to spend much time debating about the views of divorce and remarriage in the Jewish, Greek, and Roman worlds. It was pretty much a given that when the people of that time and place heard the word “divorce,” there would be an automatic assumption that divorce granted the right to remarry. To call a separation from a spouse which does not include the right to remarriage a “divorce” is an oxymoron. The relevant point for our discussion is that we can assume that the hearers of Jesus and Paul would assume that a “divorce” included the right to remarriage. If it did not, that point would have to be made very explicit.

We also do not have to spend much time on the views of the ante-Nicene church (before 325 AD). They are a rather confusing muddle of views: anti-marriage asceticism, marriage as a necessary evil for the sake of children, as well as more scriptural views. Even if it could be demonstrated that the view which became the Catholic view (divorce but no remarriage) was dominant in the early church, this would not carry much weight for answering our questions about the propriety of remarriage after divorce, because their views were not founded on Scripture. It is disappointing how early doctrinal corruption and confusion entered the church.

If we were trying to determine whether the Lutheran view of justification by faith alone or the Catholic view of justification by faith and works was the biblical view, the testimony of the early church would not be on the Lutheran side. The wrong view of justification was already present in first-century Galatia to such an extent that the first major church council was necessary to try to beat it back (Acts 15). The seeds of the coming hierarchicalism were already visible in Diotrephes’ love of the primacy (3 John 9). A hierarchical role for bishops was already entrenched in the church during the first three centuries.

Perhaps the saddest irony in church history is that numerically speaking, the theological approach of the Judaizers won. It won out in the Orthodox and Roman churches. A successful counter-attack which brought Pauline theology back to the fore would have to wait for the arrival of Luther.

The only one of the three lines of evidence that is decisive for us is “what do the relevant passages say—and what do they not say?” If we are going to formulate and enforce rules for Christian discipline, those rules must be based on clear statements from the relevant passages, not on “probably” and “maybe.”

Preliminary Issues

Exceptions to the Rule

The first and most important question is whether there can be exceptions to biblical rules, and whether there is any tension or contradiction between statements of a biblical rule which mention no exceptions and restatements of the same rule which refer to exceptions. It is clear from Scripture that there is no tension or contradiction between these two types of passages.

A prime example would the 3rd commandment in Exodus 20.

Remember the Sabbath day by setting it apart as holy. 9Six days you are to serve and do all your regular work, 10but the seventh day shall be a sabbath rest to the Lord your God. Do not do any regular work (malakah), neither you, nor your sons or daughters, nor your male or female servants, nor your cattle, nor the alien who is residing inside your gates.

This passage is written in a way that seems to leave no room for exceptions. We have to look at other passages to provide us with examples of exceptions to the Sabbath rule: “Do not do any regular work on the Sabbath.” The most notable exceptions to the rule are 1) priests working in the Temple on the Sabbath; 2) the Son of Man healing people on the Sabbath; 3) his assistants picking the grain they needed to sustain themselves as they accompanied him during his missions on the Sabbath, and 4) even pulling your son or ox out of a well on the Sabbath (Matthew 12:1-8, Mark 2:23-28, Luke 6:1-5: Luke 13:15 & 14:5). If we understand the principle, “the Sabbath was made for man, not man for the Sabbath,” we will have a good guideline for recognizing other valid exceptions that we may encounter. Incidentally, Jesus makes it clear that the principle that there may be some exceptions to a biblical rule applies not only to the rule “do not work on the Sabbath” but also to the rule “laypeople must not eat the Bread of the Presence” (Matthew 12:3-4).

Old Testament Israel had a strict religious calendar. The Passover had to be celebrated on the 14th of Nisan and the penalty for failing to do so was severe, but there were exceptions for extenuating circumstance (Numbers 9:1-13)

Numbers 9:10-13

10and told him to tell the Israelites this:If any one of you or your descendants is unclean because of contact with a dead body or is on a distant journey, he may still observe the Passover to the Lord. 11Such people are to observe it during the second month, on the fourteenth day, at twilight. They are to eat it with unleavened bread and bitter herbs. 12They must not leave any of it until morning. They are not to break a single one of its bones. They are to observe the Passover according to every regulation for it.13But anyone who is clean and is not on a journey yet fails to observe the Passover will be cut off from his people. He will bear his sin because he did not present the offering of the Lord at its appointed time.

When Hezekiah tried to restore wayward Israelites from the Northern Kingdom by inviting them to his Great Passover (2 Chronicles 30), the weakness of these people led to violations of a number of the stipulations for the Passover, but their celebration was accepted.

It is a sound rule that believers in the Lord should not bow down in heathen temples. But Na'aman was granted an exception or dispensation of sorts because of his exceptional situation. Technically speaking, Na'aman would be bowing in a heathen temple, but he would not be bowing down to or worshipping their gods (2 Kings 5:17-19).

Then Na'aman said, “If you do not want anything, please give me, your servant, as much dirt as two donkeys can carry, for your servant will never again burn incense or sacrifice to other gods, but only to the Lord. 18But may the Lord forgive your servant this one thing: When my master goes into the house of Rimmon to bow down there and he supports himself on my arm, then I too have to bow down in the house of Rimmon. When I bow down in the house of Rimmon, may the Lord forgive your servant this one thing.”

19Then Elisha said to him, “Go in peace.”

The Old Testament laws were applied with the same spirit as Jesus’ rule: “The Sabbath was made for man, not man for the Sabbath.” Another way is saying this is that “God desires mercy, not sacrifice.” As we struggle with this issue, we do well to remember that marriage was made for man (male and female). Marriage was created to serve the good of man and woman. The purpose of the institution of marriage was to serve man and woman; man and woman were not created to serve marriage.

The State of the Controversy

A trend in recent Evangelicalism is to reject the long-time Evangelical consensus that although the Bible makes it clear that 1) all divorce involves sin, and remarriage without the death of their spouse involves people in adultery; 2) there were nevertheless exceptions to this rule, which allowed remarriage by an “innocent party” if a person’s first marriage had been broken by the sexual sin of their spouse or by malicious desertion.

A key step in this movement was the 1984 book by William Heth and Gordon Wenham, Jesus and Divorce: The Problem with the Evangelical Consensus, which denied the permissibility of remarriage as long as a former spouse was alive. Heth recanted his position (although somewhat hesitantly) in 2002. John Piper was another prominent Evangelical who advocated the no-remarriage position, but his practice was rejected by his church. A 2024 book, Divorce and Remarriage In Early Christianity, by A. Andrew Das, is another entry into the debate. For an overview of the debate see Divorce and Remarriage: Four Christian Views, edited by H. Wayne House (1990).

The view which some Evangelicals are now rejecting can legitimately be called the Lutheran/Reformed/ Protestant understanding of the biblical teaching of divorce and remarriage. Some opponents of the consensus like to point to the humanist Erasmus as the person who led the way in rejecting the Catholic view, but it is highly unlikely that Luther was significantly influenced by Erasmus in adopting his own understanding of divorce and remarriage. His view came from a scriptural restudy of the Catholic marriage laws. In the Treatise, par. 78, the Lutheran Confessions reject the tradition which forbids an innocent party to remarry after divorce, on the grounds that it is one of the unjust marriage laws of the papacy. The Westminster Confession adopts a similar position. “In the case of adultery after marriage, it is lawful for the innocent party to sue out a divorce, and after the divorce to marry another, as if the offending party were dead” (WC 24, 5). For many evangelical Christians the issue of remarriage after divorce is not only an exegetical and pastoral issue but also a confessional issue.

The Method of Research

The debate often becomes entangled with negative biblical criticism. Some writers spend considerable time on the order and priority of the Gospels and on the results that the search for the “historical Jesus” has had on our understanding of texts in the Gospels. However, if the divorce and remarriage passages in Matthew, Mark, Luke, and Paul were authoritative, inspired Scriptures, breathed out by the Holy Spirit, it does not matter in what order they were committed to paper. Each is equally authoritative and must be treated on its own merits. After we have done that, we can compare them for variations of wording. Getting caught up in the “historical Jesus question” simply creates unnecessary questions and raises more doubts about the passages in peoples’ minds. Such considerations may be necessary for academic respectability, but they are not very helpful for pastoral study of the issue at hand and for comforting troubled consciences.

Grammatical and historical studies are useful tools, but the original recipients of the Gospels and centuries of readers after them did not have these tools as they sought to understand the Gospels. We should focus on the method those readers used to understand the text: 1) carefully read and meditate on the passages in their context (both immediate and wide); 2) if you are struggling to understand the passages, prayerfully restudy the passages; 3) if you are still struggling, repeat steps one and two; 4) if you are still struggling, repeat steps 1-3 as often as necessary.

The Chief Passages

Now we will turn to the chief passages. Since they are all equally inspired, we will consider the books in the order in which the church has traditionally listed them: Matthew, Mark, Luke, and 1 Corinthians.

Passages in Matthew with Exceptions

Matthew is the only Gospel that mentions exceptions to the basic principle established at creation: there should be no divorce, and there should be no remarriage before the death of one’s first spouse.

Matthew 5:27-28, 31-32

The setting of this text is the spiritual guidance that Jesus provided to his disciples in the Sermon on the Mount. The purpose of this section of the sermon is to teach his disciples that sin is not limited to outward disobedience to the law, but sin includes every violation of the law in one’s heart.

You have heard that it was said, “You shall not commit adultery” (Οὐ μοιχεύσεις) 28but I tell you that everyone who looks at a woman with lust has already committed adultery with her (ἐμοίχευσεν αὐτὴν) in his heart.

Adultery is not limited to the act of sex with a married person. Such a physical act would be both a sin and a civil crime punishable by death. Jesus shows that adultery includes also evil thoughts and desires for adulterous behavior. Such adultery in the heart is not a civil crime subject to punishment, but it is sin.

Jesus applies the same distinction between legal and moral guilt to the subject of divorce and remarriage later in the chapter.

31It was also said, “Whoever divorces (Ὃς ἀπολύσῃ) his wife must give her a certificate of divorce” (ἀποστάσιον) 32But I tell you that whoever divorces his wife, except for sexual immorality (παρεκτὸς λόγου πορνείας), causes her to be regarded as an adulteress (ποιεῖ αὐτὴν μοιχευθῆναι). And whoever marries the divorced woman is regarded as an adulterer (μοιχᾶται)

NIV 11 But I tell you that anyone who divorces his wife, except for sexual immorality, makes her the victim of adultery, and anyone who marries a divorced woman commits adultery.

NIV 84 causes her to become an adulteress

ESV But I say to you that everyone who divorces his wife, except on the ground of sexual immorality, makes her commit adultery, and whoever marries a divorced woman commits adultery.

CSB But I tell you, everyone who divorces his wife, except in a case of sexual immorality, causes her to commit adultery. And whoever marries a divorced woman commits adultery.

The first term that needs comment is ἀπολύω. The verb means to loosen or to set free. The application of this Greek term is not limited to divorce. The simplest understanding is that the use of this term for divorce implies release from all obligations to the marriage.1

1 We can say that New Testament Greek has no word for “divorce” that is a technical term that is limited only to divorce. The words used for divorce are more generic in meaning.

The two chief disputed issues here are “what is included in porneia?” and “what is the force of the two verbs for adultery?”

The three translations chosen for comparison with the EHV all correctly understand porneia as a term for sexual morality that includes but is not limited to adultery. Reams of argument have been written concerning this term, but we will not review them here. A goal of some in the “no remarriage party” is to define porneia as narrowly as possible to minimize room for exceptions.

Students of the New Testament have long been puzzled by the strange passive verbal construction in Matthew 5:32 (ποιεῖ αὐτὴν μοιχευθῆναι). The correct interpretation of this verb is important because of its key role in the debate about Jesus’ teaching concerning divorce. In their translations of this verb, the EHV and the NIV 11 regard the adultery in this verse as something that is imposed on the woman. NIV 84, ESV, and CSB regard the adultery as a sin committed by the woman.

Is the passive verb μοιχευθῆναι (moicheuthenai) to be translated as an active when it is used in reference to a woman, that is, “to commit adultery,” as NIV 84, ESV, and CSB do? This would mean that the husband who divorces the woman, even if she is an innocent victim of his adultery, “causes her to commit adultery.” The text does not explain how her husband does this, but some advocates of the “Catholic” position add an explanation: he does this by putting her in a position in which she might commit adultery by remarrying.

It is true that a passive verb form may be used in reference to a woman who is committing an act of adultery:

John 8:3-4 Then the experts in the law and Pharisees brought a woman caught in adultery (ἐπὶ μοιχείᾳ κατειλημμένην) and had her stand in the center. 4“Teacher,” they said to him, “this woman was caught in the act of committing adultery (ἐπʼ αὐτοφώρῳ μοιχευομένη).

It is not clear why the same Greek verb may be used in the active voice when a man commits adultery and in the passive voice when a woman does. Perhaps it is because the man is seen as delivering the adulterous act and the woman as receiving it. In this verse, however, the middle/passive form may remind us that adultery requires reciprocal action of more than one person, and in John 8 it may prompt the question, “I see you have brought the woman. Where is the man?”

But the explanation that a man can cause an innocent woman to commit adultery by divorcing her does not seem to be in harmony with the context of Matthew 5 nor with the rest of Scripture. Some commentaries and translations therefore render this verb as a true passive, with an expression like “he causes her to be stigmatized as an adulteress.” The literal rendering would be “he makes her adulterated.” Other shades of meaning are attempts by the translator to suggest how she is “adulterated.” The point is that the English rendering should reflect the passive.

Some light may be shed on this perplexing problem by another strange verb which occurs in Deuteronomy 24:4, a hutqattel of the verb טמא, “be unclean.” אטמ (tama) is a very common root that may refer to ceremonial or moral uncleanness.

There are only four hutqattel forms (also called hothpa'al) in the Old Testament.

Leviticus 13:55 Then after the contaminated material has been laundered, and the priest examines it, even if he discovers that the contamination has not changed its appearance and the contamination has not spread, it is unclean. (There is a second, parallel form in v 56.)

Isaiah 34:6 The sword of the Lord is covered with blood. It is coated with fat.

In both of these cases the verb describes something that has been done to the subject rather than something done by the subject. We would therefore expect that the force of the parallel form in Deuteronomy 24 would be similar.

If this is true, Deuteronomy 24:4 could be translated something like “she has been put on display as unclean.” This was done by her first husband’s act of divorcing her (at least in the eyes of some observers). This uncleanness did not result from an act of immorality by the woman nor from her marriage to a second husband, but from the public declaration about her that had been made by her first husband when he divorced her. In Deuteronomy 24, the woman in question is not forbidden to remarry after her first or second marriage. She is only forbidden to remarry her first husband who had caused her to be labeled as unclean by his divorce action against her. The prohibition of Deuteronomy 24 is directed against her first husband, not against the woman. (More will be said on the significance of Deuteronomy 24 in the discussion of Matthew 19 which follows. Here the only issue is the significance of the verb.2)

2 A fuller study of the hutqattel and its implications in Deuteronomy 24 may be found in Hebrew Studies, 1991, p 8-17.

It seems preferable not to be too specific about the shade of meaning of the verb beyond recognizing that the adultery is something done to the woman. The EHV (causes her to be regarded as an adulteress) and NIV (makes her the victim of adultery) both recognize this.

The puzzling passive construction in Matthew 5 may be an attempt to express a grammatical and moral situation which is very like that in Deuteronomy 24, which seems to be the passage that lies behind Jesus’ discussion. A selfish husband is laying a verdict of uncleanness on the woman by his act of divorcing her. Greek had no verbal form exactly parallel to the hutqattel of the Hebrew, but the writer of the Gospel is trying to express a similar thought with the closest form which he had available to him. One could even say that he had to create a special form.

Some have argued that the hutqattel (ha;M;F'hu) could mean that “she was made to defile herself,” but the parallel with the other hutqattels points to the meaning “she was defiled.” Sorting out the nuances and overlaps of the Hebrew t-infix verbs is notoriously tricky, but it seems that if the reference was to her “defiling herself,” a hithpael or maybe even a niphal with middle force would have been the way to do that.

One other thing to note is that the construction in Matthew is not a bare passive form. The construction is introduced by the helping verb “to make or to do” (ποιέω). This verbal pattern with ποιέω at times can refer, not to something done to a person, but to something attributed to or charged to a person. In John 5:18 Jesus enemies accuse him of “making himself equal to God.” Their charge is not that he is actually becoming equal to God, but that he is claiming equality with God. In 2 Corinthians 5:21 when God makes Jesus become sin, he does not make Jesus sin, but he imputes our sin to Jesus. Imputing sin to a person may also be the force of the strange verb in Matthew 5.

The interpretation of the puzzling verb in Deuteronomy 24 may shed some light on the puzzling verb in Matthew 5. The force of the hutqattel may be one more bit of grammatical information to be considered by advocates of translating Matthew 5:32, her husband “causes her to be looked upon as an adulteress and whoever marries her is looked upon as an adulterer.” This would have approximately the same force as the hutqattel in Deuteronomy 24.

Another Troublesome Verb

Equally problematic is the second verb in Matthew 5:32, μοιχᾶται (moichatai). Many sources say that this is a deponent verb, and they define a deponent verb as a verb that has a middle form but an active meaning. This explanation is incorrect. These so-called Greek deponent verbs do not have an active meaning. They all (or at least, almost all) have a middle meaning, but this often does not show up in English translations because English does not have a sophisticated (complicated) system of middle forms. In English I can say, “The barber shaved me” or “I shaved” (two active verbs), but in a system that uses middle verb forms, the second verb would have to be a middle form meaning “I shaved myself.” In English, however, it usually is translated “I shaved.” The Hebrew verb for “swear” (shb‘ ) is used as a middle-passive niphal. In English it may simply be translated “I swear,” but it has a connotation something like “I take an oath upon myself.” It seems that if the intended connotation was “an oath was imposed on me,” a hiphil would be used, but these forms are not always strictly distinguished.

Some scholars of New Testament Greek go so far as to say that there are no deponent verbs in NT Greek.3 All of these are middle-passive, with middle the more common sense.

3 Look for online articles on “deponent verbs.” You will find some that debunk the whole notion of deponent verbs. Examples are “Your Greek Teacher Was Wrong. Deponent Verbs Do Not Exist” by Danny Zacharias and “Ancient Greek Voice” by Carl Conrad.

It is notoriously hard to pin down the exact force of Greek middle verbs; the sense must be determined almost entirely by context. The forms themselves do not indicate shades of meaning. Included among the many recognized classes of middle verbs in Greek are “verbs expressing naturally reciprocal events” such as meet, fight, greet, wrestle, embrace, quarrel, converse, agree, and mate. It seems that this is a class to consider in Matthew 5:32. It is difficult to specify the exact middle connotation of this verb here. Context is the only determiner.4

4 The same is true of many other areas of Greek grammar. Some grammars may list twenty kinds of genitives, but all of these have the same form. When the interpreter calls one a “subjective genitive,” and another an “objective genitive,” he is simply identifying the meaning he deduced from the context.

Since the two verbs in Matthew 5:32 seem to be parallel, EHV translates them in a parallel way. Whatever uncertainty there may be about the shading of the middle, what can be said is that neither of these verbs is an active verb. Since they are in parallel sentences, both should be the same voice, although middle and passive forms are sometimes interchangeable.

Of the dozens of translations on Bible Gateway, the vast majority translate Matthew 5:32 with two active verbs. This is surprising since most of the churches using these translations did not ban all remarriage after divorce. This anomaly between their translations, which seemed to ban remarriage, and their practice, which allowed it, likely was a trigger, maybe even the trigger of the current controversy in Evangelicalism concerning divorce and remarriage. Only the EHV, GW, and NOG have a consistent middle/passive translation of this verb pair. NIV strangely has a split decision between middle and active.5

5 The NIV strangely corrected the first verb in 5:32 to a passive sense (perhaps on the basis of a suggestion from WELS) but left the second verb unchanged, creating a clash.

Practical Implications

So what would be the practical implications of the EHV and NIV translations?

It was also said, “Whoever divorces his wife must give her a certificate of divorce.” 32But I tell you that whoever divorces his wife, except for sexual immorality, causes her to be regarded as an adulteress. And whoever marries the divorced woman is regarded as an adulterer.

A man who divorces his wife must give her a written divorce that frees her from obligations to the marriage. Whenever such a legal divorce occurs, there are a number of possible scenarios.

The woman may have been guilty of adultery in the first marriage. But that is not the case here, because the focus here is on the result of the divorce, not on something that happened during the first marriage.

A second possibility is she was not guilty of unfaithfulness, but was wrongly released/dismissed from the first marriage. Nevertheless, a charge or suspicion of adultery would still cling to her, because the assumption of the public would be that the husband had just grounds to send her away. The EHV translation envisions a situation like that. The exception clause leaves open the possibility that one or more of the persons in the second marriage was not a perpetrator of adultery but a victim of it. (We will deal with the possible exceptions later.)

Is it, however, possible that a woman commits adultery by a second marriage after a divorce? Certainly! If all four spouses in a planned spouse swap agreed to the two divorces necessary to legalize the swap, and these divorces happened before they had committed physical adultery with each other, the two divorces would free the four from legal adultery but not from moral adultery. If they were all co-conspirators, both the woman and her new husband, her former husband and his second wife would all be guilty of adultery in their second marriages. All four of them would be adulterers who have violated the covenant of marriage. But this kind of scenario does not fit the situation here. In the situation described in this paragraph, no one would be “making the woman commit adultery.” She would be a co-conspirator in adultery.

It is quite troubling to have so much uncertainty about such key verbs, but it is important to remember that none of these passages are setting up a catalog of grounds for legitimate divorce and remarriage. They are just statements about what may happen in a divorce. They may suggest or hint at what some exceptional cases may be, but Jesus’ statement is not setting up a code book of legitimate grounds for divorce which make remarriage permissible. Jesus’ use of the law in Matthew 5 is as a mirror that exposes sin. He is not trying to set up a guide book for permissible remarriage without the death of one’s first spouse. He notes in passing that there are exceptional cases in which remarriage does not make a person an adulterer, but he gives us no rule book. (We will have to deal with the issue of exceptions further after we have looked at the other passages.)

Matthew 19:1-9

In Matthew 19 the setting is in Transjordan late in Jesus’ ministry. Jesus is responding to a trick question from the Pharisees: “Is it lawful for a man to divorce (ἀπολῦσαι) his wife for any reason?” Whether Jesus gives a strict answer or a liberal answer, he will offend some people.

4He answered, “Haven’t you read that from the beginning their Maker ‘made them male and female,’ 5and said, ‘For this reason a man will leave his father and mother and remain united to his wife, and the two will be one flesh’? 6So they are no longer two, but one flesh. Therefore what God has joined together, man must not separate.”

7They asked him, “Then why did Moses command a man to give her a certificate of divorce and send her away?” (δοῦναι βιβλίον ἀποστασίου καὶ ἀπολῦσαι αὐτήν)

8Jesus said to them, “Because of your hard hearts, Moses permitted you to divorce your wives, but it was not that way from the beginning. 9I tell you that whoever divorces his wife, except on the grounds of her sexual immorality (μὴ ἐπὶ πορνείᾳ), and marries another woman is committing adultery” (μοιχᾶται).

Some witnesses to the text add the words: and the one who marries the divorced woman also commits adultery.

Though the Pharisees’ question about grounds for divorce was not sincere, it is an important question for Christians, who know how littered with broken promises and broken hearts our society is as a result of a loose practice of divorce. The rabbinical schools of Jesus’ day were divided on the question. The rabbi Shammai took the words of Moses in Deuteronomy 24 about “finding something indecent” in a strict sense, though he did not restrict it to literal adultery. The rabbi Hillel took the words so loosely that a wife’s act of burning dinner was sufficient grounds for divorce. (There is some question whether the difference between the two schools is as distinct as some make it.) Jesus calmly bypasses the trap they have set for him. He cuts through their code-book mentality. Instead he goes to the heart of the matter, “what was God’s intention when he created marriage?”

The passage from Deuteronomy 24:1-4, to which the Pharisees seem to be alluding, makes no attempt to answer the question, “What are valid grounds for divorce?”

When a man takes a woman and marries her, if she is not pleasing to him because he has found something indecent (עֶרְוַ֣ת דָּבָ֔ר) about her, and he writes her a divorce document (סֵ֤פֶר כְּרִיתֻת֙) and hands it to her and sends her out of his house, 2and she leaves and moves on and becomes the wife of another man, 3and then that second man hates her and writes her a divorce document and hands it to her and sends her out of his house, or perhaps the second man that took her as a wife dies, 4in these circumstances her first husband, who sent her away, cannot take her again as his wife after she was stigmatized as impure (הֻטַּמָּ֔אָה), because that would be detestable to the Lord. You must not attach guilt to the land that the Lord your God is giving you as an inheritance.

NIV: after that she is defiled; ESV: she has been defiled, CSB: after she has been defiled. All four translations understand the uncleanness as something that has been done to the woman.

Moses permits legal divorce and remarriage, but he places a restriction on it by banning remarriage to the first spouse after a divorce and a subsequent remarriage.6 If a man insisted on divorcing his wife, he had to sign a legal document (סֵ֤פֶר כְּרִיתֻת֙) that protected the right of the woman to remarry, and he could never remarry her even if her second spouse died.

6 While writing this paper, I accidently ran across a law of Kentucky banning a man from marrying the same woman more than three times. I have no idea whether this was inspired by the Deuteronomy law or was original work.

The civil laws of Moses did not command divorce. They did not even approve of divorce. They regulated it. In Deuteronomy 24 the exception to the rule is not an exception that allows remarriage. Remarriage after divorce is assumed as the regular rule. The exception to the general rule in this passage is a ban on one form of remarriage. This type of remarriage is banned even if the woman’s second marriage had been dissolved by death.

Leviticus 21 is another passage that seems to assume the right to remarriage as the regular rule.

7[The priests] shall not marry a woman who has been a prostitute or is defiled. Neither shall they marry a woman divorced (גְּרוּשָׁ֥ה) from her husband, for each priest is holy to his God.

13The high priest shall marry a woman who is a virgin. 14A widow or a divorcée or a woman defiled because of prostitution―these he shall not marry. Instead, he shall take a virgin from his own people as a wife, 15so that he does not defile (וְלֹֽא־יְחַלֵּ֥ל) his offspring among his people, for I am the Lord, who sets him apart as holy.

The rules for priests seem to assume that the right of remarriage for divorcées and widows is the regular practice for most people. If such remarriage was already banned, it would not be necessary to enact an exception to the rule for priests.

In Matthew 19 Jesus states that according to the order established by God at creation there should be no divorce. Only death legitimately ends a marriage. The civil law of Israel however allowed divorce because of the hardness of people’s hearts. In some cases, a divorce was a lesser evil than forcing the continuation of a violent marriage. A divorce gives a legal right to remarry. It does not necessarily give a moral right. Exceptions to the principle that remarriage without the death of a spouse is adultery may result when the first marriage has been ended as a result of the sexual immorality of one party. Jesus is not writing a law book here, so he offers little explanation of such circumstances. He is not inviting people to a “look for loop-holes mentality.”

Passages in Mark and Luke with no exception mentioned

Mark 10:1-11 seems to be the same incident as Matthew 19. The key verse lists no exceptions clause.

11He said to them, “Whoever divorces his wife and marries another commits adultery against her (μοιχᾶται ἐπʼ αὐτήν). 12If she divorces her husband and marries another, she commits adultery” (μοιχᾶται).

The two verbs have a middle/passive form. Is the force of the verbs here distinguished from active?

If a man wrongfully divorces his wife and remarries, he is guilty of adultery even if no act of adultery preceded the divorce. The same rules apply to women as to men.

Luke 16:18 is a stand-alone comment with no additional context. It may be from the same time period and circumstances as Mathew 19 and Mark 10.

Anyone who divorces his wife and marries another is committing adultery (μοιχεύει), and the man who marries a woman divorced from her husband is committing adultery (μοιχεύει).

The two verbs are active forms. Do μοιχᾶται and μοιχεύει have exactly the same force?

The point of contrast in these two passages is the absence of an exception clause. Based on an alleged priority of Mark, some scholars suggest that Mark provides the original teaching of Jesus, and Matthew is an attempt by the church to soften that teaching. It seems more likely that Jesus comments on exceptions in Matthew because in the Sermon on the Mount, he is giving practical pastoral instructions for believers rather than simply deflecting a hypocritical question from his enemies. Matthew 19 includes a more extended discussion with his disciples than the relatively brief treatment in Mark and Luke.

All the passages make the point that in God’s plan marriage is to be a life-long union of one man and one woman. Breaking that union and marrying another is adultery. Two of the Gospel passages state that there are exceptions to that rule of no legitimate remarriage without the death of the previous spouse. This may happen in cases in which a divorced person has been a victim of sexual sin by their first spouse. There is however little elaboration on what those exceptions may be. Jesus may have felt a need to mention exceptions, so that his statement of a complete ban of remarriage in principle would not be understood as an absolute ban in practice.

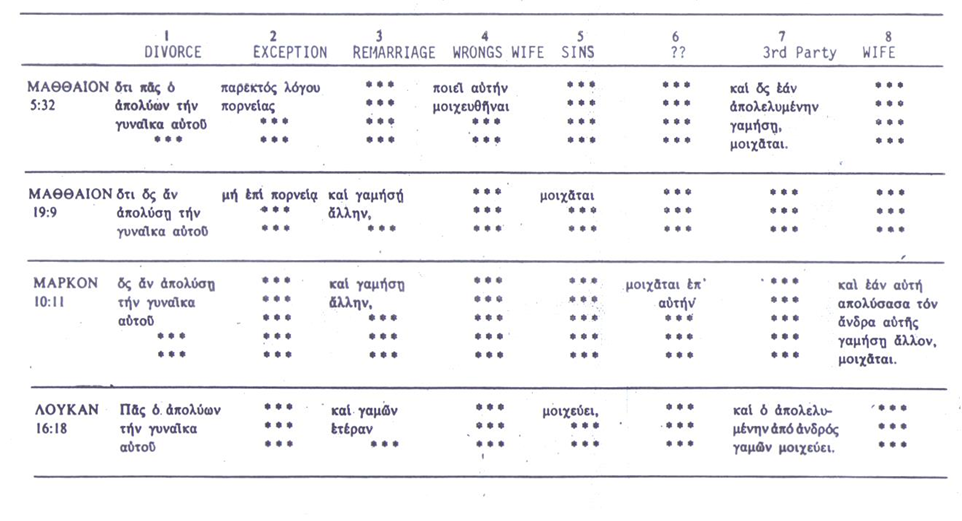

Chart of the Gospels Passages

Marriage is a life-long union legitimately broken only by death.

Civil divorce dissolves a marriage contract. It does not necessarily give moral freedom to enter a new marriage.

The two passages in Matthew give an exception to this principle of no remarriage in cases in which a marriage was broken by sexual sin (Column 2)

People may wrong a spouse by adultery or illegitimate divorce (Columns 4 and 6)

The same rules apply to women and men.

A Second Cause for Exceptions?

In the so-called Protestant view, it has usually been stated that Scripture allows two causes for exceptions to the normal rule which is: “no divorce and remarriage without the death of one’s spouse.” The first cause is sexual sin by one’s spouse which broke the first marriage. The second cause that allowed remarriage is being a victim of malicious desertion by one’s spouse. This second cause has been based on Paul’s extensive discussion of marriage in 1 Corinthians 7.

Celibacy, Self-Control, and Marriage71Now concerning the things you wrote: It is good for a man not to touch[] a woman. 2But because of sexual sins, each man is to have his own wife, and each woman is to have her own husband. 3The husband is to fulfill his obligation to his wife, and likewise the wife to her husband. 4The wife does not have authority over her own body—her husband does. Likewise, the husband does not have authority over his own body—his wife does. 5Do not deprive one another, unless you both agree to do so for a time, in order to devote yourselves to[] prayer and then come together again, so that Satan does not tempt you because of your lack of self-control. 6However, I say this as a concession, not as a command. 7For[] I wish all people were like me, but each person has his own gift from God. One person is blessed in this way, another in a different way.8I say to the unmarried and to widows that it is good for them if they remain as I am. 9But if they do not have self-control, they should marry, because it is better to marry than to burn with desire.

One of the reasons for marriage after the Fall into sin is to give a proper outlet for the natural sexual desires. Spouses have a sexual duty to each other. Remaining unmarried is a good state, but if anyone cannot restrain their sexual desires while living in an unmarried state, they should marry. While this verse does not directly address the issue of remarriage following a divorce, it presents an issue that must be considered. Can people be forced to remain unmarried if doing this does not guard them against sexual sin?

10Next I command the married (it is the Lord’s command not mine): A wife is not to leave (μὴ χωρισθῆναι) her husband 11(but if she does leave, she is to remain unmarried or be reconciled to her husband), and a husband is not to divorce (μὴ ἀφιέναι) his wife.

The first verb, χωρισθῆναι, is passive/middle in form.

The second verb, ἀφιέναι, is active. Its usage is not limited to divorce but may refer to many types of sending away or release.

Here Paul states the same principle Jesus taught in the Gospels. (We do not know what form of Jesus’ teaching the churches had at the time 1 Corinthians was written. Luke 1 mentions that a number of accounts of Jesus were in existence while he was writing his Gospel (perhaps in Aramaic.)

12But I, not the Lord, say to the rest: If any brother has an unbelieving wife, and she is willing to go on living with him, he is not to divorce (μὴ ἀφιέτω) her. 13If any woman has an unbelieving husband, and he is willing to go on living with her, she is not to divorce (μὴ ἀφιέτω) her husband. 14For the unbelieving husband has been sanctified in connection with his wife, and the unbelieving wife has been sanctified in connection with her husband. Otherwise, your children would be unclean, but as it is, they are holy. 15But if the unbeliever leaves (χωρίζεται,), let him leave (χωριζέσθω). The brother or the sister is not bound (οὐ δεδούλωται) in such cases, and God has called us to live in peace.

Divorce would be a form of “leaving,” but it is not the only form. If the unbeliever insists on leaving, the believer is no longer bound or enslaved to the marriage. A person who is not bound (δέδεται) is free (ἐλευθέρα ἀπὸ τοῦ νόμου) to remarry (Romans 7:1-3).

Now Paul deals with a question about divorce and remarriage which Jesus had not discussed, but which has arisen in Corinth. If a couple had married when they were non-Christians and after that only one spouse becomes a Christian, is the marriage broken by the heathen character of one spouse? The answer is “No.” Marriage is an earthly contract, and the bond of marriage is not broken by a change in faith. A Christian wife should not leave her pagan husband. But what if he is unwilling to have a Christian wife and he deserts her? “If the unbeliever leaves (χωρίζεται), let him leave (χωριζέσθω). The brother or the sister is not bound (οὐ δεδούλωται) in such cases.”

Believers whose unbelieving spouse has ended the marriage need not feel conscience-bound to remain in that broken marriage because of the possibility that the unbelieving spouse might be brought to faith. A believing spouse may hope that the unbelieving spouse will eventually become a believer in Jesus if the marriage is continued, but there is no assurance that this hope will be realized. Malicious, persistent desertion breaks the marriage bond, so a deserted partner is not bound to remain in the marriage and may obtain a legal divorce. Divorce includes a right to remarry.

Paul follows with a long discussion of pros and cons of entering marriage or remaining unmarried in the circumstances that the Corinthians were facing. At the end of this section he makes another statement that is relevant to the issue of remarriage.

39A wife is bound (δέδεται) to her husband for as long as he lives, but if the husband has died, she is free (ἐλευθέρα ἐστὶν) to be married to any man she wishes, only in the Lord (μόνον ἐν κυρίῳ).

Some understand “only in the Lord” to mean that “she must marry only a Christian,” but this adds a restriction that is not explicit in the text. As a child of God, whatever she does, she will do with the Lord in mind. She can enter only a marriage that honors God’s principles for marriage. She cannot for example enter a marriage that will make her a party to adultery or that does not accept the biblical principles of marriage as a life-long union.

Summary

All the Gospel passages make the point that marriage is to be a life-long union of one man and one woman. Breaking that union and marrying another person is adultery. Two of the Gospel passages state that there are exceptions to that basic rule of no remarriage. This happens if a divorced person has been a victim of sexual sin by their first spouse. There is, however, little explanation of what those exceptions may be. Jesus may have felt a need to mention the exceptions when talking to his disciples, so that his general statement that God’s will from creation is that there be no divorce and remarriage would not be understood as a total ban of divorce and remarriage in civil practice. Jesus is not attempting to throw out the divorce and remarriage practices of Israel or to set up a rulebook.

Obstacles to the Neo-Evangelical Rule of No Remarriage after Divorce

The Nature of Divorce

The right of divorce and remarriage were the assumed standard in the world of Jesus and Paul. In fact, the right to remarry is part of the essence of a divorce statement. Can one speak of a “divorce” in the strict sense of the word that does not include the right to remarry?

Exceptions to the Rule

Biblical rules, even the 3rd Commandment, sometimes had exceptions, even though those exceptions are not mentioned in the law itself. Scripture itself mentions some exceptions in other passages.

New Understanding of NT Greek Verbs

Criticism of the EHV translations of the passages in the Gospels does not reflect an adequate distinction between active, middle and passive verbs in Hebrew and Greek. This applies especially to a misunderstanding of the nature of so-called “deponent” verbs.

There Are Exceptions

There are two clearly stated exceptions to the rule that every divorce and remarriage without the death of one’s spouse is adultery: 1) “except in cases of sexual sin” and 2) “if the unbeliever departs, let him depart.” The biblical texts offer no detailed definition of the scope of these exceptions.

Porneia includes physical adultery but it is not limited to it. It includes other forms of sexual contact as well. In some cases, the line may become blurry. Looking at porn might begin as adultery in the heart, but if it becomes an addiction that breaks the marriage bond by depriving the wife of what she is to receive from her husband, has the behavior gone beyond Matthew 5:27 to Matthew 5:31-32?

The definition of malicious desertion is even more of a slippery slope. Malicious desertion must be permanent and willful. Stomping out of the house after an argument does not establish malicious desertion. Does the offender have to leave the premises to desert a marriage? If he drives the wife out of the house so he can live there himself, hasn’t he left the marriage? Refusal of sex which is habitual and willful is forsaking the marriage. We will not attempt to discuss all kinds of possible forms of desertion thereby creating a kind of mini-lawbook. Actually even a 500-page volume of cases would not be a solution. The only viable way is that in every case, all the parties examine the situation in the spirit of self-examination which Jesus teaches in Matthew 5. In every case, even if there has been unquestioned wrong-doing, the first avenue to explore is repentance, forgiveness, and reconciliation. In some cases there is a danger that persons will be looking for reasons to divorce their spouse, elevating misdemeanors into felonies because they want a divorce, but they want to pin the blame on their spouse. An example at the other end of the spectrum would be the offending husband demanding that the wronged wife must remain in the marriage although he broke the bond. Honest, deep self-examination on the basis of the biblical principles is the only way to prevent these and other similar errors.

This may be the hardest section of pastoral theology. It would be nice if we had a rulebook so that all we had to do was look up the appropriate case-law. But God has left us with the principles and with the responsibility to apply them. When Heth recanted from his anti-remarriage position, he said he was not sure that his decision to recant was correct. He very likely was troubled that his decision to recant might be undermining Scripture’s strong warnings against divorce, but he could not find enough evidence to justify labeling as adulterers the victims of a wrongful divorce who remarried.

Most roads have a ditch on each side. Here, on one side of the road is the ditch of a casual attitude of easy divorce for virtually any reason. On the other side of the road, is the ditch of burdening people’s consciences with rules against remarriage that have no clear evidence in Scripture. The involved parties must wrestle with the case. For example, a pastor who was the victim of an unscriptural divorce might feel that he should not remarry as his testimony to God’s ideal for marriage. That would be good example of dedication to the principle of life-long marriage. What would not be a good example would be for him to pass judgment on another pastor in a similar situation, who made the opposite decision because of different circumstances.

Being on a slippery slope beside a ditch is not a comfortable place to be, but if our mission is to rescue people, we can’t avoid venturing onto slippery slopes. It’s an occupational hazard for rescue workers that if you are trying to pull people out of the ditch, you are going to get mud splashed on you. That rule applies here.

In hard cases, err on the side of mercy rather than the side of the letter.

The Bottom Line

Those who want to dump the Evangelical consensus claim to have demonstrated 1) that Jesus did not allow any remarriage of divorced parties without the death of the first spouse, and 2) that participants in such second marriages are living in adultery. What is the pastoral application of this theory for Evangelical Christians? Pastors could of course refuse to officiate at such second marriages. But what if they encounter Christians living in such marriages? Though some adherents of the “Catholic view” might counsel separation from the second marriage, others would allow people to continue in such marriages. So the advice is that people should be taught that such marriages are continuous adultery, but they can continue to live in them (How can this be??) It is difficult to see an essential difference between this proposed solution and an annulment or an indulgence theory. To work so hard to demonstrate that such remarriages are adulterous, but then to allow people to continue to live in that way of life if they show a sufficient degree of repentance—how does this help troubled consciences find peace? Advocates of the revisionist view can find no evidence that Jesus, Paul, or the early church ever broke up such “adulterous marriages.” (How could they, since they must have realized that going back to the first spouse would clash with Deuteronomy 24?) The bottom line is to brand such remarriages as adulterous, but to allow people to remain in them if they are sufficiently repentant. The rule “go and sin no more” seems to be set aside. The suggested solution seems more legal than evangelical. It is hard to understand how this will comfort troubled consciences. Its effect on troubled consciences is the chief reason to be concerned about the Neo-Evangelical rule.

If a pastor encounters a couple living in a second marriage in which one of them was guilty of adulterous conduct in entering the marriage, the right counsel is to tell them to repent and to be faithful in the marriage where they are now, and to make the necessary apologies and requests for forgiveness to those whom they have wronged. It is wrong, however, to attribute such guilt to those who were victims of a divorce and not the perpetrators of a divorce.

This FAQ was written purely on the basis of a study of the passages. The FAQ mentioned in passing that “the exceptions clause view was the historical Lutheran and Evangelical view.” After the completion of the FAQ, we found and appended these lists of historical quotations that demonstrate that claim.

Appendix

Martin Luther from Luther’s Works, vol 36.

As to divorce, it is still a question for debate whether it is allowable. For my part I so greatly detest divorce that I should prefer bigamy to it185; but whether it is allowable, I do not venture to decide. Christ himself, the Chief Shepherd, says in Matt. 5[:32]: “Every one who divorces his wife, except on the ground of unchastity, makes her an adulteress; and whoever marries a divorced woman commits adultery.” Christ, then, permits divorce, but only on the ground of unchastity. The pope must, therefore, be in error whenever he grants a divorce for any other cause; and no one should feel safe who has obtained a dispensation by this temerity (not authority) of the pope. Yet it is still a greater wonder to me, why they compel a man to remain unmarried after being separated from his wife by divorce, and why they will not permit him to remarry. For if Christ permits divorce on the ground of unchastity and compels no one to remain unmarried, and if Paul would rather have us marry than burn [1 Cor. 7:9], then he certainly seems to permit a man to marry another woman in the place of the one who has been put away. I wish that this subject were fully discussed and made clear and decided, so that counsel might be given in the infinite perils of those who, without any fault of their own, are nowadays compelled to remain unmarried; that is, those whose wives or husbands have run away and deserted them, to come back perhaps after ten years, perhaps never! This matter troubles and distresses me, for there are daily cases, whether by the special malice of Satan or because of our neglect of the Word of God.

185 As he actually did later in the case of Henry VIII and Philip of Hesse, considering it to be the lesser of two evils insofar as it was not without divinely sanctioned precedent in the Old Testament

(Martin Luther, Luther’s Works, Vol. 36: Word and Sacrament II, ed. Jaroslav Jan Pelikan, Hilton C. Oswald, and Helmut T. Lehmann, vol. 36 (Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1999), 105–106.)

The Lutheran Confessions

78] Indeed, since they have made certain unjust laws concerning marriage and apply them in their courts, the establishment of other judicial processes is required on these grounds as well. For the traditions concerning spiritual relationship are unjust,68 as is the tradition that prohibits remarriage of an innocent party after divorce.69 Unjust, too, is the law that in general approves all secret and deceitful betrothals in violation of the rights of parents.70 The law requiring celibacy of priests is also unjust. These ecclesiastical laws hold more snares for consciences, but there is no need to recite them all here. It is enough to have made it clear that there are many unjust papal laws concerning marriage and that on this account the magistrates must establish other courts.

68 German: “the prohibition of marriage between baptismal sponsors is unjust.” See Gregory IX, Decretalium IV, 11.

69 The church Fathers based their position forbidding remarriage after divorce on Matthew 5:32*; Mark 10:11*; Luke 16:18*. See Gratian, Decretum II, chap. 32, q. 7, c. 1–8, 10.

70 Gratian, Decretum II, chap. 30, q. 5, c. 1–3. See, for example, Luther’s 1530 tract On Marriage Matters (WA 30/3: 205–48; LW 46:259–320).

(Robert Kolb, Timothy J. Wengert, and Charles P. Arand, The Book of Concord: The Confessions of the Evangelical Lutheran Church (Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press, 2000), 342–343.)

Martin Chemnitz, Examination of the Council of Trent, II

Let us see further what Christ Himself in His response understands by divorce or repudiation. In Matt. 19:9; Mark 10:11; Luke 16:18 He links these two: to put away his wife, and after the divorce to marry another. Therefore the definition of divorce is the same in the question of the Pharisees and in the answer of Christ. We shall apply this meaning of divorce to the question itself and to the answer. For the Pharisees are asking for what causes a divorce may be permitted. Here I freely confess that if Christ had answered only what Mark and Luke describe, the sense would simply be this, that such a divorce is not lawful for any cause whatsoever, but that, no matter what befell, it is not permissible for the bond of marriage to be dissolved except through death. For the words read thus: “Whoever divorces his wife and marries another commits adultery.” But because it is a universal and necessary rule in reading the evangelists that the true interpretation and meaning must be sought and taken from a comparison of the descriptions found in the other evangelists, for they render each other aid in this way, that what one stated more briefly and obscurely the other complements and explains more clearly—therefore also the description of Matthew must be compared, which testifies, not once but in two places, that Christ, on different occasions, when He treated the matter of divorce, expressly added as an exception the cause of fornication (Matt. 5:32; 19:9). Therefore the statement of Christ in Mark and Luke are not simply universal but are to be taken with the exception which the apostle Matthew, who was present at these discourses, adds in two places.

Now because it is a wholly true rule that something is taken away from a general statement by a particular case, the meaning of Christ’s answer, according to a comparison of the evangelists, will be this, that only in the case of fornication is a divorce, such as we have described above, lawful and that in all other cases it is not lawful that a man should send away his wife and marry another. And because He declares that adultery is committed if someone marries another, He shows that in all other divorces, for whatever causes they are performed, the bond of matrimony remains—with the exception of that divorce which is made on account of fornication. For the arguments taken from the contrary sense are of all arguments both the clearest and strongest. Therefore because Christ says: “Whoever divorces his wife, except for the cause of fornication, and marries another commits adultery,” therefore, from the contrary sense, whoever divorces his wife for the cause of fornication and marries another does not commit adultery.

(Martin Chemnitz and Fred Kramer, Examination of the Council of Trent, electronic ed., vol. 2 (St. Louis: Concordia Publishing House, 1999), 747–748.)

Later Dogmaticians

[6] Hollaz. (1380): “The conjugal bond between husband and wife, as long as they remain alive, is in itself indissoluble, both on account of mutual consent, and especially on account of the divine institution, Gen. 2:24; Matt. 19:6.” Br. (835): “Meanwhile, in two cases, divorce or the dissolution of legitimate and valid marriage, as to the conjugal bond itself, may occur. Without doubt, in the case of adultery, where, by the law itself, marriage both can be and is dissolved, and the innocent party is permitted to enter into another marriage (Matt. 19:9; 5:32), and in a case of malicious desertion (1 Cor. 7:15), where the deserter himself actually and rashly sunders the conjugal bond, and where to the deserted party, when a competent judge makes the declaration, the power belongs to enter into a new marriage.” The reason why a divorce may be granted under these two conditions, lies in the very nature of the case.

(Holl. Hollazius. Br. Baier. Heinrich Schmid, The Doctrinal Theology of the Evangelical Lutheran Church, Verified from the Original Sources, trans. Charles A. Hay and Henry E. Jacobs, Second English Edition, Revised according to the Sixth German Edition (Philadelphia, PA: Lutheran Publication)

Appendix 2 Additional Quotations from Luther

From Luther 1522:

Here you see that in the case of adultery Christ permits the divorce of husband and wife, so that the innocent person may remarry. For in saying that he commits adultery who marries another after divorcing his wife, “except for unchastity,” Christ is making it quite clear that he who divorces his wife on account of unchastity and then marries another does not commit adultery.

(Martin Luther, Luther’s Works, Vol. 45 : The Christian in Society II, ed. Jaroslav Jan Pelikan, Hilton C. Oswald, and Helmut T. Lehmann, vol. 45 (Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1999), 30–31.)

From Luther 1523, exposition of 1 Cor 7: underlined below

But when both are guilty and both run away, it is fitting that they both cancel their wrongs, become reconciled, and sit together again. And this teaching of St. Paul should be stretched to cover all sorts of divorces; for example, if a man and wife run away from each other not because of his or her Christian faith but because of some other matter, be it anger or any other dissatisfaction, then we should teach that the guilty party reconcile himself or remain unmarried and that the innocent mate be free and have authority to remarry if the other will not be reconciled. For this is all unchristian and heathen, that a spouse runs away from his mate out of momentary anger or any other dissatisfaction, refusing to share fortune and misfortune, the sweet and the sour, with his partner—as he is obligated to. Such a spouse is truly a heathen and unchristian.

(Martin Luther, Luther’s Works, Vol. 28: 1 Corinthians 7, 1 Corinthians 15, Lectures on 1 Timothy, ed. Jaroslav Jan Pelikan, Hilton C. Oswald, and Helmut T. Lehmann, vol. 28 (Saint Louis: Concordia Publishing House, 1999), 38.)

From Luther 1530:

I am writing here for pious, good consciences, where one of these has found some great, permanent defect in his betrothed, with which he would never have knowingly accepted her; he has been deceived and ought to be free to marry another. The canon laws even state that error and conditio dirimunt contractam, but because that same law allows divorce to the masses in general only on condition that no one may remarry, we consider such a divorce to be worthless, indeed, pure deception dangerous to the soul and the conscience. Therefore if anyone wishes to make use of this law, let him do so; we do not wish to use it according to our conscience, for it is utterly useless for dealing thoroughly and conclusively with marriage matters.

(Martin Luther, Luther’s Works, Vol. 46: The Christian in Society III, ed. Jaroslav Jan Pelikan, Hilton C. Oswald, and Helmut T. Lehmann, vol. 46 (Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1999), 303.)

From Luther in that same article in 1530

Accordingly I cannot and may not deny that where one spouse commits adultery and it can be publicly proven, the other partner is free and can obtain a divorce and marry another man. However, it is a great deal better to reconcile them and keep them together if it is possible. But if the innocent partner does not wish to do this, then let him in God’s name exercise his right. And above all, this separation is not to take place on one’s own authority, but it is to be declared through the advice and judgment of the pastor or authorities, unless like Joseph one wanted to go away secretly and leave the country. Otherwise, if he wishes to stay, he is to obtain a public divorce.

But in order that such divorces may be as few in number as possible, one should not permit the one partner to remarry immediately, but he should wait at least a year or six months. Otherwise it would have the evil appearance that he was happy and pleased that his spouse had committed adultery and was joyfully seizing the opportunity to get rid of this one and quickly take another and so practice his wantonness under the cloak of the law. For such villainy indicates that he is leaving the adulteress not out of disgust for adultery, but out of envy and hate toward his spouse and out of desire and passion for another, and so is eagerly seeking another woman.

(Martin Luther, Luther’s Works, Vol. 46: The Christian in Society III, ed. Jaroslav Jan Pelikan, Hilton C. Oswald, and Helmut T. Lehmann, vol. 46 (Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1999), 311.)

From Melanchthon: Loci Communes 1543

The Time after Which It Is Permissible to Remarry

If a divorce has taken place because of adultery, no time is prescribed for the innocent party after the legal judgment has been made.

But in a question of desertion it is necessary to consider the years, in order that the person may be understood as really having been deserted, and that the desertion has not simply been deceitfully concocted out of bad faith or lack of serious intent.

The law in the Codex [book 5, section 1, law 2] grants a woman the right to remarry after two years. But if the husband is not outside of the province and does not give his consent to this arrangement, then a public rite of marriage must be deferred for a longer period.

The regulations of the papacy do not even permit remarriage for the innocent party at any time, unless it is evident that the deserting party is dead. But I have cited above the statement of Paul from Corinthians [1 Cor. 7:15] which frees the innocent person, and at the same time the deserting person becomes guilty of adultery. Therefore, in no way are the innocent parties to be burdened with chains for wrongdoing. But we must also in this case understand that the liberation is not merely an empty word, but that the person who has been liberated from the marriage bonds is permitted to marry.

Justinian expressly permits a deserted person to remarry after ten years. In a gloss in the small chapter “In Our Presence” in the Decretals he says, “In cases where after seven years there is demonstrable presumption of the death of the husband, the woman may be excused if she remarries.” The gloss is milder than the text. But when the judge has investigated the matter and determined that the complaint about desertion is not a mere pretext, and sees that the morals of the innocent person are upright, he can follow the law of Constantine regarding the four-year waiting period, or the statement concerning a five-year period which appears in the following section under the title “Concerning Divorce.”

This moderation of the law does not seem to be unreasonable. Nor will I prescribe a definite period. But a prudent judge will consider both what he needs to teach by way of example, and that undue burdens should not be placed on the conscience of the innocent party.

(Philip Melanchthon and Jacob A. O. Preus, Loci Communes, 1543, electronic ed. (St. Louis: Concordia Publishing House, 1992), 255–256.)